Mansfield Park is a complicated novel, to put it succinctly. It is a Cinderella story stripped of all the sparkly affectations and magical sense of the fantastic, and dipped in the dark murkiness of topics like adultery, passivity, religion and morality. Here is a novel where Jane Austen steps outside her comfort zone of the bright and airy, and presents to us a Cinderella named Fanny Price who is moral yet passive, endearing yet not very likeable. Like Fanny’s female cousins in the novel, I didn’t have very much to say to her.

Impecunious Fanny leaves her home in Portsmouth to the palatial Mansfield Park, under the aegis of her rich uncle and aunt, Sir and Lady Bertram. It is an arrangement negotiated by her aunt Norris who is perhaps one of the nastiest literary creations ever, but is all the more astringent because she springs forth from the usually bright pen of Jane Austen. The Bertrams are not bad people, rather, they are rich people. Their attitude towards a young Fanny is one of, well, apathy would be too strong a word. Let it instead be said that Fanny fits into their world without disturbing a thing. Fanny Price, let the reader be aware, is no Elizabeth Bennett. She is, instead, possessed of a timorous disposition. As a child, she is quickly prone to tears, and as an adult, she is physically weak, though her initial timidity somewhat blossoms into an elegant taciturnity. Fanny’s cousins, Maria and Julia, do not play the conventional “ugly stepsisters”, rather, they ignore Fanny. This makes sense because Maria and Julia are vivacious, beautiful and poised for brilliant futures attained, of course, by marrying well. Though Fanny is indispensible to her enervated Aunt Bertram, she never really receives matronly affection from her. Her Aunt Norris, on the other hand, constantly reminds the girl of how inferior she is to her cousins, and how grateful she must be to them for their charity. In all of this, Fanny’s only true friend is her cousin Edmund who always takes up for her in instances where Fanny is wronged, or just plain ignored.

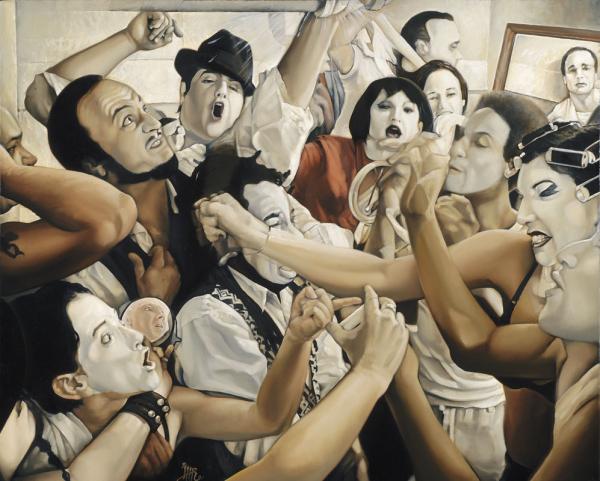

Things get increasingly complicated once this cast of characters grows up. Maria finds herself betrothed to the wealthy, socially relevant, but very boring Mr. Rushworth. Edmund has resolved to become a clergyman, (the hereditary title of ‘Sir’ being destined for the elder, pleasure-seeking, Tom) Julia dreams of a success similar to Maria’s, while Fanny reads. The patriarch of the family, Sir Thomas Bertram, leaves to tend to his slave-run estate in Antigua, and, in his absence, enters the witty, worldly, brother-sister pair of Mary and Henry Crawford. Worldly, urban, well-spoken and fashionable, the Crawfords arrive as a whirlwind that places the young aristocrats of Mansfield Park on a “very serpentine course” lined with temptation, lies and ulterior motives. I enjoyed how Austen uses the theatre to reveal the true tensions between the characters, as they rehearse a play called Lover’s Vows that they put on for a lark, exclusively amongst friends. The enamoured pair of Henry Crawford and Maria excessively rehearses their parts, while Maria’s conflicted, jealous fiancée stumbles over his lines, and is constantly bitched about, mainly pertaining to what a poor actor he is. Edmund and Mary, cast as lovers, give voice to their true passion for one another, but realize that theirs is a love that can never work because of Mary’s finely etched vision of the kind of life she hopes to lead. Despite the fact that, at this point, the novel is heavy with activity and full of brilliant if controversial conversations about issues ranging from men, women and love to the role of the clergy in society, it is the well-intentioned silences of one Miss Fanny Price that evoke the most intrigue. Fanny finds the business of staging a play scandalous and immoral, she finds Henry Crawford deplorable for his lothario act with her betrothed cousin, but, almost on a penitential instinct, she never really allows herself the luxury of voicing these opinions. This moral priggishness can be very annoying, but it is also very real: one does have opinions on what is morally wrong or right, but this impulse To Be Good i.e. to avoid unpleasantness is so strong within one that one’s silence essentially becomes a straitlaced kind of hypocrisy that one never really recognizes in one’s character.

I also enjoyed the use of letters as a device to convey the presentiment and the aftermath of major scandals. I understand that many Austen loyalists were hoping for high, eloquent drama, as far as the scandals were concerned, and, no doubt, Austen would have crafted those exquisitely, but the epistolary route is a far more judicious one. As Austen herself says in the novel: “Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery. I quit such odious subjects as soon as I can, impatient to restore everybody, not greatly in fault themselves, to tolerable comfort, and to have done with all the rest.” Personally, as a product of an age where all I would have to do would be to glance at Maria Bertram’s status updates to map out her goings-on, I find that the letters, the perpetual anticipation between letters and reading between the lines and the biases of the writer, afforded me a rare, delicious pleasure.

All in all, Mansfield Park is complex, sophisticated, and morally effusive without being officious, but also problematic. I called it a Cinderella story because I got the sense that passivity is the ‘virtue’ being rewarded in this novel, that one is a better person for one’s privations in life. To me, Mansfield Park poses the following question: Is it morally right for one to sit by, holding one’s ethical convictions close to one’s heart, as the universe mold itself around you only to recompense you in the end, for Being Good?

Until the next time,

GossipGuy!